Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are advised that the following article and video may contain names, images and voices of people who have died.

By Nichola Davies / LGAQ Digital Journalist

Outside the Hope Vale Aboriginal Shire Council building in Cape York flies the flag of another council. It’s one that’s 1,500 kilometres south of the township, or 16.5 hours by car—a lot more via a WWII-era train.

The Guugu Yimithirr people have inhabited the Hope Vale and surrounding region for tens of thousands of years and played a pivotal role in the formation of modern Australia, hosting Captain James Cook and his beached ship Endeavour at present-day Cooktown for seven weeks in 1770.

During this time, Captain Cook recorded 150 words of the Guugu Yimithirr language, and one of those words is spoken across the world today: the word gangurru, or kangaroo.

Forty-five kilometres north-west of Cooktown is Hope Vale, which was originally established as Hope Valley Mission by German Lutherans at nearby Cape Bedford. The site of the town today is some 20 kilometres inland from the Cape Bedford mission and was chosen after the community returned after being forcibly removed during WWII.

Government suspicions of Germans and others deemed ‘enemy aliens’ were rife in Australia during WWII and led to the imprisonment of thousands of people in internment camps. On 11 May 1942, the Department of Native Affairs ordered the evacuation of Hope Valley Mission, with army trucks rolling in six days later. The town’s prolific German Reverend Georg Schwarz was arrested, and a harrowing experience followed for residents.

Reverend Schwarz with his wife and daughters in Hope Vale. Image courtesy State Library of Queensland.

Aboriginal artist Roy McIver was born on the mission in 1934 and was a child when he was removed. In his artist’s statement for the etching ‘The Removal’, he said, “Suspicions about the loyalties of the German-Lutheran mission prompted allegations of a possible invasion, supported by Aborigines, and that our people would use bush expertise to lead the Japanese soldiers through unchartered territory.

“Many people died as a result [of being removed], including my sister Emily.”

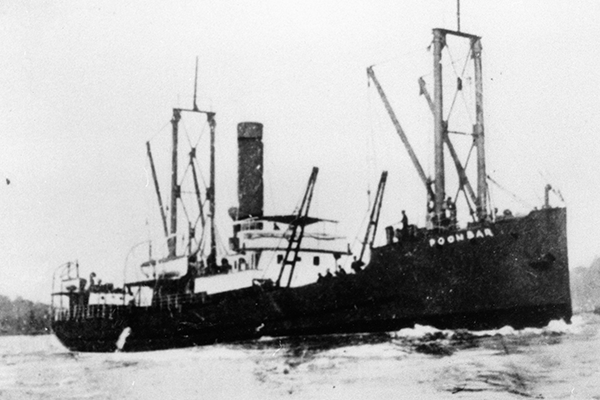

Hope Vale Mayor Jason Woibo said of the removal, “They were forcibly removed by the government and the army and taken on a boat down to Cooktown—the Poonbar.”

The Poonbar. Image courtesy State Library of Queensland.

At Cooktown, they waited 24 hours without food or water before being taken to Cairns.

“From Cairns, they were taken down to Woorabinda on a train, which is where they spent about eight, nine years,” Mayor Woibo said.

“While in Woorabinda, 87 people passed on within the first several months of being there.

Men from Hope Valley (now Hope Vale) at the Woorabinda Mission in 1948. Image courtesy State Library of Queensland.

“The climate is completely different to what it is like up here, and basically they were taken with what clothes they had on their back. So, they had no food, no clothes, basically nothing.”

When the war was over, a small cohort of Hope Valley residents were sent home to establish the community again.

“So different groups came back at different times and started working on what we all call home today—Hope Vale,” Mayor Woibo said.

“Coming back to Hope Vale was an exciting time for all of our Elders.

“They spent a lot of their time down there worrying about home, and for them to get the news to travel back to Hope Vale again, the community were excited—they were crying, they thought that they would never see this place again. And their excitement, they couldn’t contain it, to travel back here to their land.

“Some stayed in Woorabinda, some stayed in other communities, but most came back, came back home.”

By the time residents returned to Hope Vale, there were other people living there, and a package of land where modern-day Hope Vale was negotiated.

“Its first name was the Valley of Hope so that then turned into Hope Vale, because when they came back they looked at this valley and said well, this is the hope that we have now,” Mayor Woibo said.

Fortunately, the land is very fertile and good for growing crops, unlike the original site at Cape Bedford. In Hope Vale now, there are big blocks for houses where residents grow their own veggies in their backyards.

Hope Vale landscape. Nichola Davies / LGAQ.

Mayor Woibo said that the common goal of returning home unified the community, which comprises 13 different clan groups.

“Everyone’s worked together for the best outcome of Hope Vale,” he said.

“They helped each other where needed, and they went above and beyond supporting each other to come back home and make Hope Vale the place it is now—one that I’m proud to be a councillor and mayor of.”

Hope Vale Aboriginal Shire Council is a financially sustainable council that’s extremely well run and has a host of community services, from child care to aged care, health and sports, cafes and vibrant tourism offerings from its Arts & Cultural Centre to its Maaramaka Walkabout tours.

The church in Hope Vale. Nichola Davies / LGAQ.

The Mayor describes Hope Vale as a forward-thinking and progressive community, one that has been developing this way for many years.

“We’ve got to pay respects for previous councillors that have come through, who’ve established where we are now,” he said.

“I think they’ve done a really great job in bringing the community of Hope Vale to the position it’s sitting in, and we’re hoping that we can keep that momentum going as the new council.

“We’re really enjoying our time here at the moment, and we’re hoping for better luck in the future, but we’re here to help build Hope Vale and keep Hope Vale going in a positive direction.”

Visitors to Hope Vale are greeted with signage featuring Hope Vale's totems - black and white cockatoos. Nichola Davies / LGAQ.

2022 marked 80 years since the removal of the people of Hope Valley, and Hope Vale and Woorabinda have been close ever since. Mayor Woibo says Woorabinda holds a special place in Hope Vale’s heart, referring to Woorabinda as a sister or brother because of the way the people of Woorabinda took in the people removed from Hope Vale.

“For the 50-year anniversary of the return to the community, Hope Vale went down to Woorabinda and celebrated down there, so hopefully when the 80 years comes around, we can celebrate the return of the Guugu Yimithirr people in Hope Vale,” Mayor Woibo said.

It’s in homage to its history—not forgetting the past but remembering, celebrating and building something better—that Hope Vale flies the Woorabinda Aboriginal Shire Council flag alongside its own, alongside the Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, Queensland, and Australian flags, outside the council building.

Hope Vale Mayor Jason Woibo stands outside the council building in Hope Vale. Nichola Davies / LGAQ.