© Queensland Museum, Peter Waddington

By Judith Hickson / Queensland Museum Curator, Social History

As deeply personal and, generally, highly valued objects, pocket watches were often handed down as family heirlooms and are represented in many museum collections. One of these small treasures came to light recently in Queensland Museum’s horological (the study of time) collections.

The pocket watch, made in the late 1700s by a London watchmaker, Richard Haywood, was donated to the Museum in 1912 by former Brisbane Municipal Mayor, Robert Woods Thurlow (1855-1913). Mayor Thurlow was the inaugural President of the Local Authorities Association which, in time, became the Local Government Association of Queensland.

Aged, cracked, and showing signs of wear and tear, the watch has remained tucked away in the Museum’s vault, undisturbed and unexamined for over a century.

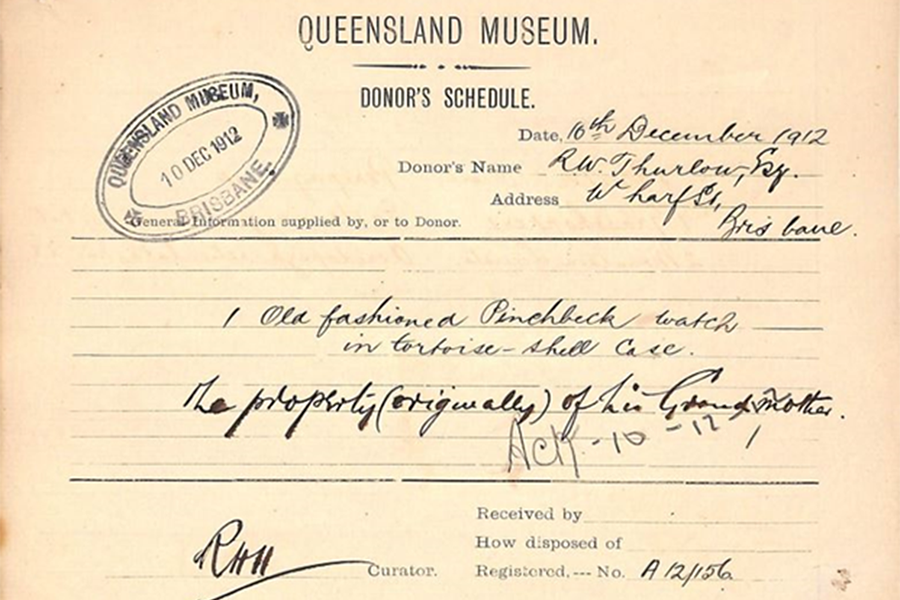

The original donation schedule for R W Thurlow's watch

Featured here is a copy of the original donation schedule for the watch. The initials ‘RHH’ are those of Ronald Hamlyn-Harris, a former director of the museum from 1910 to 1917. A later, rather cryptic addition, notes that the watch had once belonged to Mr Thurlow’s grandmother.

Apart from his name and the date of his donation, the document offers little clue to Mr Thurlow’s personal history or contribution to this city’s municipal life. Moreover, without a name or indication of his grandmother’s identity or place of origin, there was little evidence to begin our search, but for a barely discernible, hand-written engraved signature, ‘A M Woods’, and a date, ‘May 1843’, inside the watch case.

© Queensland Museum, Peter Waddington

Colonial ‘Cabinets of curiosities’

As was common in the colonial era, museum exhibitions were, literally, ‘cabinets of curiosities’ where dedicated curators worked to collect, preserve and fill the museum’s display cabinets with artefacts, objects and specimens of interest to themselves, to other researchers and to their audiences.

In many instances, collections from phases of a museum’s development can be easily ascribed to the collecting passions of the director and the principal curators of that time.

As an entomologist, Hamlyn-Harris’ primary interest was in expanding the natural history—biological and botanical—specimens and growing the scientific focus of the museum. He was also instrumental in expanding the anthropological and ethnographic collections; social history was not among his collecting passions.

Over the past century and a half, however, Queensland Museum’s social history collection has significantly expanded and practices have changed to meet standards set by Australian and international museums.

Today, objects are required to be thoroughly researched and meet strict criteria, including documented provenance (chain/proof of ownership) and history, before they are acquired for the State collection.

Now, as social historians and caretakers of the past, our job is to uncover the histories of the objects we collect. When we come across undocumented objects like the pocket watch, we try to fill in the missing pieces from whatever information is available.

Questions we might ask are: Who owned the object? Is the item historically significant? Is it rare? Where did it come from and who made it? Does it relate to a particular place, time, event or person in Queensland’s history? Does it have potential for scientific or historical research?

This process takes time, but we do this to develop a better understanding of the object itself, and also to uncover a more personal story or connection to a broader history—details that add meaning and significance to what we collect.

If we’re able to find them, family members, descendants and/or acquaintances are often the most reliable sources of information and indispensable to our research. Fortuitously, our search for information about R W Thurlow soon led to the article published in a previous edition of Council Leader magazine by his great-great grandniece, Cheryl Gray. As a family member and keeper of family history, Cheryl and her brother Graham Thurlow have already helped fill some important gaps in what little we know of this watch’s history.

We are only at the beginning of our investigation, but we hope that, with further research and the family’s help, the forgotten lives of this well-worn object and its former owners will begin to take new shape in the public imagination.