Words - Nichola Davies

Images - State Library of Queensland

For soldiers who were lucky enough to return home to Queensland from fighting on the front lines in World War I, the excitement of seeing loved ones again turned to sorrow as many learned their mothers, fathers, siblings and wives had died, or would soon die, from Spanish Influenza.

The outbreak of the Spanish Influenza in Queensland coincided with a time in Australian history where the fledgling federation of the states meant there was little time to truly establish themselves and iron out not only interstate co-operation but co-operation between local and state governments.

Patrick Hodgson says in his thesis on the subject that the Queensland State Government was unprepared to deal with the crisis of the Spanish Influenza on the ground, considering local governments to be the ideal vessel to combat the epidemic, as well as to mobilise the thousands of volunteers that would be needed. This was convenient for the State Government as it now only had to bear a reduced cost, putting one-third of the onus on local councils (much to their outcry that they could not afford it), but also as they remained in power through State Government-appointed health inspectors in each district.

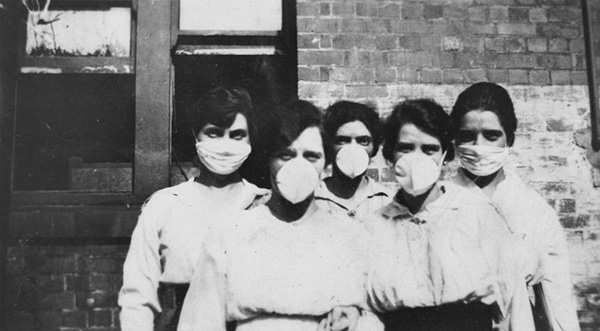

Five women are standing in front of a brick building, possibly a hospital, wearing surgical masks during the Spanish 'Flu outbreak in Brisbane, 1919.

The pandemic reached Australia by way of Sydney. Queensland was quick to close its borders on January 29, 1919, establishing quarantine camps along its southern boundary. The Tweed Heads Historical Society says that at the time, the nearby Queensland town of Coolangatta had no doctor, chemist, milkman, baker or school and as such many people travelled to Tweed Heads on the other side of the border for daily errands and work.

The border closure was so abrupt that many Queenslanders leaving Coolangatta in the morning and heading into Tweed for the day were left stranded until they were allowed to go home some 10 days later. Even the mayor of Coolangatta, J.T. Matters, lived in Tweed Heads, so he had to take four months’ leave.

Despite border closure efforts, two laundresses at Kangaroo Point Hospital were the first in Queensland to be officially diagnosed with Spanish Influenza in May 1919. It quickly spread to the rest of the state, hitting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island communities disproportionately hard. Of the Indigenous population at the Barambah Government Reserve in the South Burnett–now Cherbourg–69 out of the 596 residents died of the virus.

People arrive at the quarantine camp in Wallangarra during the influenza epidemic of 1919. The camp consists of tents and corrugated iron buildings, surrounded by bushland. People are waiting to be registered and admitted to the camp. They have their suitcases and other belongings with them.

The spread through regional communities was in part due to the docking of ships with infected people on board, open travel between communities, and in the case of southern Queensland, regional show days.

On December 10, 1918, The Daily Mail reported that at a meeting of the South Brisbane Council, the council discussed a letter that it had submitted to the Department of Public Health “inviting attention to the overcrowding of places of amusement, recommending that such places should be sprayed with disinfectant once every day”, also asking if some power could be obtained to disinfect pawnbrokers shops and second-hand clothing stores. In reply, the secretary advised the department had that day submitted draft regulations, which included disinfection of places of amusement.

Some months later in late May, the event of the Taroom Show, that was unfortunately given the go-ahead by the local government, meant people en masse travelled by rail from communities such as Chinchilla for a day of fun. In 1919, several Chinchilla residents infected with Spanish Influenza attended the show. Disinfection measures proved futile as by the Monday, 150 people in Taroom had the virus and by June 6 the Brisbane Courier reported that not a house in the township had escaped it. Two local councillors who were amongst those who were in favour of hosting the show–William Williams and Frederick Atkins–died within a week.

Lessons learned from the spread of the virus at shows in other places as well as the sheer amount of sick people meant the cancelling of the Ekka in Brisbane, with the Showgrounds already being used as a makeshift hospital anyway. It’s worth noting this was only one of three times the Ekka has ever been cancelled, the other two being in World War II and this year, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A large crowd of people who were working as volunteers during the influenza epidemic. The group includes, doctors, nurses, ladies and schoolchildren, pictured outside the Ithaca Women's Emergency Corps kitchen.

The State Government was hard-pressed to find enough hospital workers for Brisbane–something local councils pointed out to the State Government when being asked to prepare their own makeshift hospitals and somehow fill them with staff, and find a third of the finances required to do so to boot.

As such, local governments in regional communities, in some instances combining forces with other nearby councils combatted the disease the best they could, setting up isolation areas in their hospitals, and if these became overwhelmed, tents or taking up school buildings. Patients were also often treated in their homes.

The shortage of nurses to run hospitals and care for the sick throughout Queensland meant the local governments did indeed play a huge role in mobilising everyday people to enlist as volunteers. Women in particular were rallied to form emergency corps in their communities. One particular group, the Women’s Emergency Corps in Brisbane, brought together smaller altruistic groups for the common good. Women in the corps visited dozens of people in need every day, distributing food and performing nursing duties, with many succumbing to the disease themselves. This was carried out all over the state through different women’s groups, these volunteers saving the lives of many who would have otherwise died from the disease.

The pandemic ran its course in Queensland by 1920, and it was then up to the local and state government to rebuild their decimated communities. While we remember the war dead, there is sadly little in the collective conscience of Queenslanders about those who succumbed to the Spanish Flu, in many cases by caring for others. The COVID-19 pandemic may cause new histories on the topic to be written.